Today, June 15, is the feast day of Anglican writer and spiritual guide Evelyn Underhill. A “hinge” event for me each year, in my own spiritual calendar, is the Day of Quiet Reflection in honor of Underhill that is sponsored annually by the Evelyn Underhill Association.which would have been held this past Saturday, June 13. We had to postpone to next year because of the pandemic. A genuine loss to me among so many greater losses.

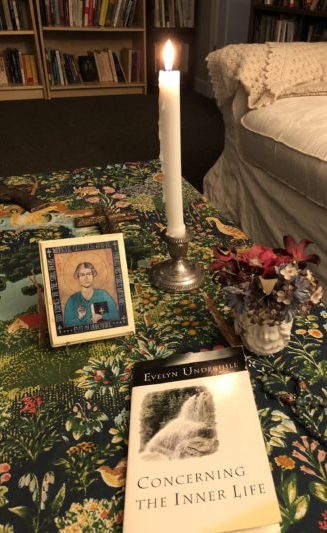

So I took a good part of the day to have my own quiet time, reading inside and outside on the deck, pausing for prayer when the invitation came, soaking in the growing things that were so important to Evelyn in so much of her spiritual writing. I had just finished reading Robyn Wrigley-Carr’s new book, The Spiritual Formation of Evelyn Underhill, a fascinating account of her relationship with her first spiritual director Baron Friedrich von Hugel, and how that relationship formed her own ministry of spiritual guidance and retreat work. Robyn’s book steered me toward Evelyn’s retreat for clergy and religious workers, Concerning the Inner Life, and I spent the day with it, prayerfully sinking in to a resource that feeds my own work of spiritual guidance.

A core teaching of all of Evelyn’s work is that the mature spiritual life is always rooted and grounded in adoration. If we begin by focusing on God, with awe and gratitude, loving and receiving love with no other agenda, then everything else follows from that: we learn to grow in communion with God’s purposes, and this will issue in whatever ministry of intercession and service we are made to carry out. But it is all rooted and grounded in prayer that is focused on God – what she elsewhere calls “contemplative prayer.” I love the way she works that metaphor of being “rooted and grounded” in God. Here’s a quote I’ve been savoring from Concerning the Inner Life: I post it here so I can keep returning to it (I’ve revised the text to remove masculine pronouns for God which some readers may find distracting)

By contemplative prayer. . . I just mean the sort of prayer that aims at God in and for Godself and not for any of God’s gifts whatever, and more and more profoundly rests in God alone: what St. Paul, that vivid realist, meant by being rooted and grounded. When I read those words, I always think of a forest tree. First of the bright and changeful tuft that shows itself to the world, and produces the immense spread of boughs and branches, the succession and abundance of leaves and fruits. Then of the vast unseen system of roots, perhaps greater than the branches in strength and extent, with their tenacious attachments, their fan-like system of delicate filaments and their power of silently absorbing food. On that profound and secret life the whole growth and stability of the tree depend. It is rooted and grounded in a hidden world. (p. 21)